- India

- International

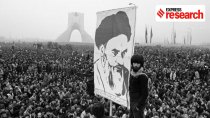

Fuelled by Pakistan's economic crisis: why is PoK on the boil?

Mumbai hoarding collapse: Two weeks ago, civic body sought to dismantle hoardings for violations

‘Exam did not go well’: 2nd NEET aspirant goes missing from Kota in a week

Explained | What are India's stakes in Iran's Chabahar port?Subscriber Only

BCCI's ask from new coach: Should be able to handle pressure of handling marquee players

Best of Premium

2 weeks before phase 3 voting, Meta flooded with communal political ads

Modi's overtures towards Pawar, Uddhav: checking 'sympathy factor', rising MVA

UPSC Key | Integrated theatre commands, Oleander flowers, Gold ETFs and more

Tavleen Singh writes: Modi on the backfoot?

Why Congress hit ‘400 paar’ in 1984 elections

What we need is a farmer-friendly agri-export policy

In Ambedkar’s birthplace, Dalits resent politics over Constitution

Toxic mothers and poor parenting in Hindi cinema and OTT content

What EC told Kharge on revised voter turnouts, how figures are arrived at

Latest News

Stock Market Today Live Updates: GIFT Nifty indicates gap-up start for Sensex, Nifty

UAE releases new AI model to compete with big tech

Meta exploring AI-assisted earbuds with cameras

Tabu to star as ‘strong, intelligent, alluring’ Sister Francesca in Dune: Prophecy series, a prequel to Denis Villeneuve’s blockbuster films

31-year-old killed, 2 family members injured in scuffle over parking car in Gurgaon

Apple set to sell Vision Pro headset outside US

Why some Indians are turning to LMIA work permits to emigrate to Canada

Pune Lok Sabha voting trend keeps candidates on tenterhook

Google-backed Anthropic releases Claude chatbot across Europe

Delhi Confidential: Nadda responds to EC notice, ball in poll panel’s court

Ludhiana admin to EC: MP Bittu occupied govt house illegally, NDC delayed over rent recovery

Kashmiri girl, who chose Tricity after terrorists entered her school campus, tops Mohali

Punjab’s women commission seeks inquiry into video showing Channi touching Jagir Kaur’s chin, she says ‘out of respect’

Punjab Lok Sabha Polls: Arvind Kejriwal, wife Sunita, Mann in AAP’s list of stars; RS members Seechewal, Mittal, Arora missing

Express Interview with Anurag Thakur: ‘Kejriwal biggest liar, no anti-incumbency against BJP in Hamirpur, country’

Heeramandi additional director on Sanjay Leela Bhansali sets: 99 retakes, 600 people, Sharmin Segal’s criticism and filmmaker’s maddening drive to perfection

TN HSE +1 Result 2024: How to check Tamil Nadu +1 marksheets at dge.tn.gov.in, tnresults.nic.in

- 2.5

- 2.5

- 1

- 1.5

Why Congress hit ‘400 paar’ in 1984 electionsSubscriber Only

Latest Video

Did Rahul Gandhi Really Stop Mentioning Adani-Ambani? | Rahul Gandhi Speech

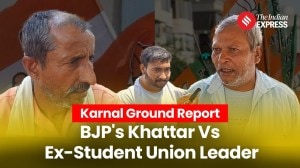

Karnal Lok Sabha: Ex-CM Khattar Vs Congress' Budhiraja: Who has the Edge?

Naveen Jindal Interview: Naveen Jindal On Haryana Farmers Against BJP

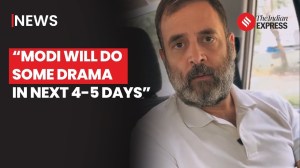

Headline: Rahul Gandhi claims PM Modi will do some “drama” to distract people

Sandeshkhali News: Woman Claims She Was Tricked Into Filing Rape Complaint

The victims — Rishabh Jasuja (deceased) and his brother Ranjak and mother Pratibha — were taken to a nearby private hospital, where Rishabh was declared dead.

Mumbai News Today Live Updates: IMD has issued a yellow warning for hot and humid conditions for Mumbai and a heat wave warning for Thane

Tibrewal, the advocate for some of the alleged victims, had last month demanded in the High Court that action be taken against complicit officials and had also prayed for the transfer of investigation to the CBI.

The polling began at 7 in the morning and picked up till 1 pm after which it slowed down for a while before again gaining momentum at the end.

The Ludhiana civic body commissioner, Sandeep Rishi, in his reply to Bittu's complaint, further submitted that in 2015, the house in question (kothi number 6, Rose Garden), was transferred by the civic body to the deputy commissioner, Ludhiana (general pool) for allotment at their level.

On Sunday, other three members of the victims' family — Sushila's husband Gopal Rajput, her brother-in-law Kishan Gujjar, and her sister Rekhaben — retreated to the beach following the high tide

The two-member team includes Inspector General (Lucknow range) Tarun Gauba and Deputy Inspector General of Police Vinod Kumar Singh, who is with the UP Police's security wing

There are seven cases pending against 'Savukku' Shankar in Chennai police's central crime branch/cyber crime out of which three are under investigation.

AP Election 2024 Live Updates: In 2019, the YSRCP won 151 of the 175 Assembly seats in Andhra.

Shreyash Lodh, 16, from NPS Koramangala topped the region with 99 per cent

The new free AI model is faster and much more capable than existing models from OpenAI.

Here are the top five viral videos of the day.

As per data shared by CBSE, this year over 39 lakh students have registered for the CBSE board exams. Students can check and download their scorecards from the official websites - cbse.gov.in, cbseresults.nic.in, results.digilocker.gov.in and umang.gov.in.

EXPRESS VIEW

Elon Musk predicted that chess will be "solved" in 10 years, sparking reactions from top grandmasters. This was triggered by his post about a device linked to cheating rumors. Musk believes computers are superior in chess and the community responds with mixed opinions, highlighting the value of human competition.